I love working with ultrasound. Diagnostic imaging devices are what most people think of when ultrasound is mentioned, but it is also widely used for analyzing body fluids, treating kidney stones, enhancing drug delivery, and managing pain. That’s why I wrote this ultrasound primer.

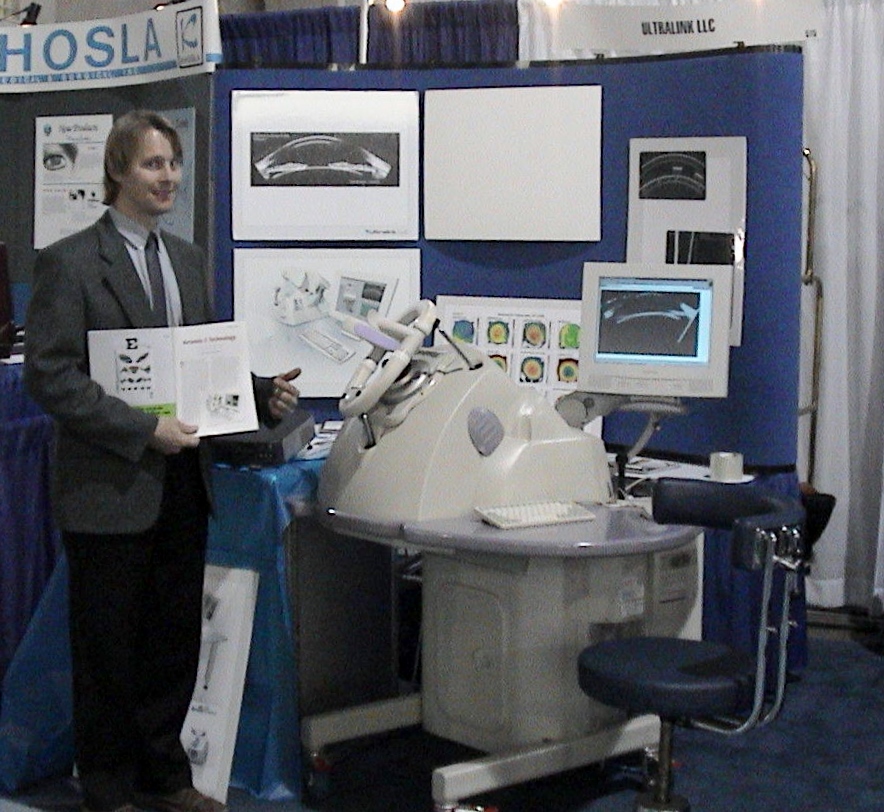

My StarFish clients have innovative as well as traditional applications for ultrasound. Those projects involve general 2D and 3D imaging, Ophthalmic and Intravascular Ultrasound, Ultrasound guided interventions, and even the high intensity and non-imaging diagnostic devices that first come to mind.

How does ultrasound accomplish all these things? Here’s an ultrasound primer:

Sound is just vibrations in materials at frequencies that we can hear (setting aside the tree-in-the-forest argument over whether there is a sound when no one is around to hear it). Ultrasound consists of the same vibrations, except at frequencies above 20 kHz – that is, higher than one can hear. Ultrasound’s versatility comes from varying the strength of the vibrations, their frequency, and the materials that are vibrating.

When used at low intensities and coupled into the body from a skin-contact transducer, ultrasound vibrations reflect off internal structures such as blood vessels and bone. By painting a picture based on the timing and strength of these reflections, one can produce the traditional B-mode ultrasound image. More advanced analysis might examine other characteristics of the echoes, for example the frequency (Doppler) shift to determine the speed of blood flow.

At higher intensities, ultrasound vibrations can heat and even break up materials. This is the operating principle for devices such as therapeutic deep-tissue heaters, and lithotripters that pulverize kidney stones.

Given the potential for harm, numerous regulatory standards set design and performance requirements for medical ultrasound devices. Some standards (e.g. AIUM/NEMA Acoustic Output Measurement Standard for Diagnostic Ultrasound Equipment) relate to how the acoustic output of a device is measured. Others (e.g. IEC 60601-2-5 Particular requirements for the basic safety and essential performance of ultrasonic physiotherapy equipment) set out safety and performance requirements for devices used in specific applications.

One of the exciting things about working with ultrasound and medical devices is how technologically sophisticated it has become. In the past we were just looking for images and creating them from plain echoes. Now there’s a lot more interest in extracting the maximum amount of information from the ultrasound itself; more than just a pretty picture, we can get a whole host of insights into the target tissue characteristics. All this is enabled by progress in integrated circuits. High speed analog-to-digital converters and signal processors can be embedded in a reasonably sized device – sometimes even a hand held one. The result is greater clinical effectiveness and information. The patient enjoys shorter time exposed to ultrasound and the overall scan experience is more pleasant thanks to more user friendly devices.

Beyond medical devices, ultrasound is used in a variety of ways. Some fairly novel applications include sorting small objects such as cells suspended in liquid, mixing immiscible reagents, and enhancing the transport of drugs across body barriers. Cleaning, inspection, distance and velocity measurement, and process acceleration are a few of the non-medical applications where a little ultrasound makes the job easier.

I hope this ultrasound primer gives you a better idea of how ultrasound works and the amazing variety of applications– just enough to get you through a medical device conference cocktail hour. I’d enjoy hearing from readers about novel applications or experiences with ultrasound.

Bjarne Hansen is an Electrical Engineer at StarFish Medical. He contributes to the design and development of ultrasound and other medical products at StarFish and particularly enjoys designing embedded systems when not sailing the Pacific or filming ultrasound expertise videos like the one below.

Images: StarFish Medical

Vibration testing is important for safety risks and for business risks Learn the XYZs of Vibration basics.