Defining scope of work: Medical device lessons from New Horizons

Earlier this year, a colleague of mine at StarFish Medical wrote about when good is good enough: I’d like to expand on those comments regarding defining scope of work, adding that good enough can be great.

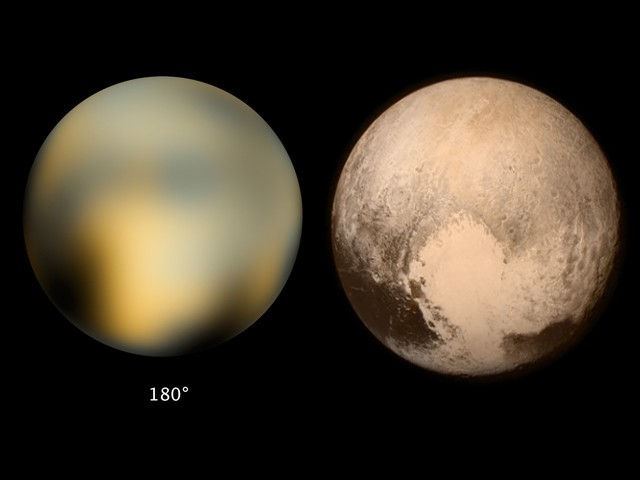

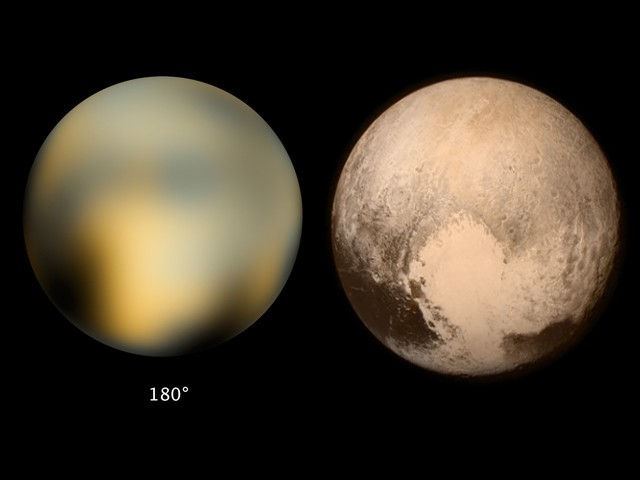

If you’ve read the news recently, you’ll know that we have for the first time, “visited” Pluto. Following in Voyager’s footsteps, the New Horizons spacecraft rocketed out to the far reaches of our solar system in a record time of 9½ years. It carried with it only seven instruments, and didn’t actually stop at Pluto, pausing only to wave hello and goodbye as the craft flew by at over 40,000 km/h.

Why not stop? Wouldn’t the opportunity to gather more data be immense? What about adding other instruments? Maybe a UV camera? Perhaps a mass spectrograph? All of those features and activities could have been justified, but scope creep could have ballooned the project to the point where it was too big for NASA to justify and eventually cancelled.

Sound familiar?

Medical devices can suffer the same fate. Defining scope of work to include pushing data to the cloud, adding wireless, rechargeable, or other features can seem like a great idea at first. But while these extra features could make for a successful device, it’s important to take a step back and think about all the additions because they add scope, they add complexity, and they can add regulatory complexity as well. It’s important to understand the development costs and timeline each feature adds to the device before moving ahead.

It may be possible to launch with a simple subset, and add more complexity in a later model. A revenue stream can be generated on a model with fewer features, which enables it to become the first-to-market. By launching a simpler device, it creates the benefit of a strong predicate for the next model.

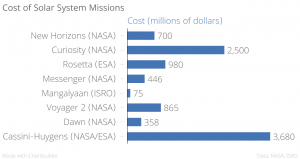

Going back to our spacecraft analogy, the earlier Cassini spacecraft was launched in 1997 (and is still functioning), with the goal of orbiting Saturn and its moons. The braking required for orbit and extra instruments it carried consumed more power, and hence required a larger power source. It weighed over 12 times as much as New Horizons, which added to the launch costs with the effect that Cassini cost more than five times that of New Horizons. NASA was willing to justify those costs at that time, but budgets change, and NASA can only support so many high-value missions. Had New Horizons increased its scope, it may never have gotten off the ground.

New Horizons is a wonderful example of why good enough can be great, and how if scope creep had been allowed to happen to New Horizons, we might not be seeing Pluto right now. Already, the first few images of Pluto have had surprises.

Dana Trousil is a StarFish Medical Mechanical Engineer. A fan of limiting scope creep and pushing the envelope, he optimizes and innovates medical devices in all of his StarFish projects.

Images: StarFish Medical