An alpha device may look like it’s finished, but it’s not a medical device.

A basic principle of medical device commercialization is that even though an alpha device looks like it’s finished – cool housing, looks like a device – it’s not a medical device until it passes regulatory standards and receives regulatory clearance, after which it’s fairly burdensome to make changes.

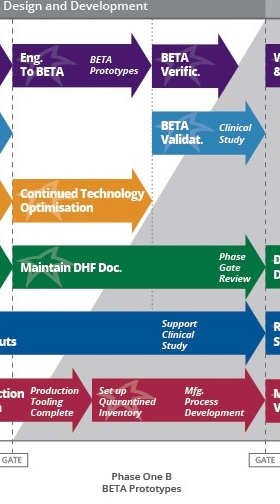

Development usually involves following a series of phases and gates that ensure a smooth transition from product definition and proof of concept through quality management, clinical trial and (finally) Health Canada, CE or FDA approval. Basically “the alpha that looks like a product” is not a product, it’s a prototype.

In some ways, we do a disservice by making an alpha looks finished; an ugly alpha would better indicate the process isn’t complete! Of course, a polished alpha is something that can be shown to investors and potential customers to generate interest and demonstrate that milestones are being achieved. So, looks can be important too. A well-developed alpha also allows for more in-depth formative studies, which is important in evaluating any GUI’s (graphical user interface), patient touch points, and other physical user interfaces. Just recognize that looks aren’t everything.

Beta Refines

Beta provides the opportunity to address any deficiencies discovered the first time a device is put together (alpha). Product development is broken down into Product Development and Product Introduction for good reasons. Before an alpha can be created, a lot of design goes into just getting the technology to work. An alpha is the first attempt at making a product; prototypes that have gone before have had different goals in mind, such as proving that the core technology is sound, or proving that the concept is viable (if we are aiming for a hand-held device, can we get the technology into something roughly hand held, or is it the size of a fridge).

Device verification or validation can’t take place until there is an alpha. Alpha is when one really learns what is wrong with the actual product. Up until this time, many of the usability and human factors may have only been assumed and not fully tested. With an alpha device, those assumptions can be challenged. But it’s the first attempt – the result will almost certainly miss some of the initial product requirements. Maybe new insight is gained and something innovative can be incorporated. In short – the device needs another spin, and that’s a beta medical device. It’s the opportunity to polish and fine tune the product so it can become a commercial success.

Beta Mitigates

If a design is not mature enough when put into the field, you will likely discover deficiencies and need to make design changes. Major design changes may require another submission or even additional medical studies. Building a beta to address those alpha issues helps mitigate the regulatory risks. You are essentially trading off early market access to avoid field deficiencies that may damage device reputation. The last thing you want is a problematic market introduction causing influencers and early adopters to believe the device is unreliable. Did you hear there was a recall?

If your design is not good enough, you have to change it.

With recent changes to ISO 62366 and FDA guidance, there is a focus on usability and human factors. Summative testing can be expensive and time consuming. By refining the device through a beta medical device, we can do some formative testing on the alpha device, refine issues, and then go into future summative testing with confidence that we won’t have to repeat expensive or lengthy summative testing.

What about a Minimal Viable Product (MVP) instead of Beta?

Let’s say you bring a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) to market instead of developing a beta. What are the odds that you will have to do another 510k? Our team consensus was just about 100 percent. If you do the minimum viable product in lieu of a beta and look at the FDA flow chart, pretty much all avenues will lead to an additional 510k.

Why? Any change in the indications for use forces another submission, as can significant changes to any patient risk. An MVP will almost certainly have reduced features, and may not be as easy to use or reliable as it would be with more iteration during development.

An MVP might work for gaining field response from early adopters, or at act a predicate for later revisions. And that can be valuable, so it is a viable strategy. But the strategy and business plan need to have contingencies for the MVP to evolve. And that will likely involve another submission.

Don’t let the look fool you

Rapid prototyping can create amazing looking prototypes, but that doesn’t make them a product. Medical devices are not the only market that creates prototypes. At the Detroit Auto Show, they have all of these fantastical creations exciting the imagination. But if you actually drove one of them off the stage, the suspension would break or the wheels would fall off. They cost a million dollars each to make, but they are concept cars. The final product based on these creations never looks exactly like these models. The product requires refinement, testing, more refinement, and even more testing before it becomes something you can buy at a local show room.

Making one of something has its challenges. Making the 200th one work and feel like the first one is an entirely different set of challenges. Beta development should use production methods and thus is representative of what the product will be. If the goal is to change production methods to achieve consistency or cost at a later date, verification may have to be repeated. Even aspects of 60601 testing may have to be repeated. Going through a beta using as close to production methodology as possible will minimize the chance that an expensive change will be required.

It’s not about alpha and beta

In some ways, it really isn’t about an alpha or beta medical device, but about achieving the product’s requirements in a way that can be reliably and consistently produced. Beta is more than just another spin; it includes verification, validation, regulatory testing, summative testing, and so forth. Can those be challenged with only one spin? Sure. But it’s exceedingly rare to hit all of the requirements in one shot. More often than not, two or more spins are required to satisfy all of the requirements. Commercialization requires meeting both regulatory as well as business requirements, and to do that, designs need the time to evolve; multiple spins aren’t gratuitous – they are a necessity. Plan for multiple spins, and your product stands a much better chance of achieving commercial success.

Learn how to get the most out of working with a contract manufacturer.

Astero StarFish is the attributed author of StarFish Medical team blogs. We value teamwork and collaborate on all of our medical device development projects.

Images: StarFish Medical