The word innovation is often thrown around like many other business buzzwords. Real medical device innovation takes effort and is truly valuable. Here are a few key ingredients that will improve the odds of achieving this elusive goal.

What is Medical Device Innovation anyway?

Recently a group of StarFish leaders went through an exercise to precisely define innovation. You’d think that would be easy, given that we pride ourselves in our abilities in this area. It took a bunch of thought and discussion, and we settled on the following working definition.

Innovation is a creative solution to a problem that provides value to customers.

Let’s dive deeper into some key points of this definition.

First, we’ve chosen to focus on the output of the process of innovating, rather than the process itself. It’s easy to muddle these concepts up. For instance, you may have heard the expression: “innovating for innovation’s sake”. This unhelpful phrase suggests that a team might be going through the motions of innovating purely so they can achieve an innovation and not for a useful purpose. By our definition, there must be a valuable purpose for true innovation. Whether or not the process of innovation is effective is a completely different conversation!

In our definition, we use the word creative in two senses. The first is that of creation – it has not existed before. The second is in the more traditional sense that it was likely the result of creative exploration. In a nutshell, if you didn’t have to create it, then it’s not an innovation.

An innovation is also a solution: there is at least one distinct problem that the innovation addresses. Typically, an innovation addresses an ill-defined, woolly problem – the sort of situation where you’ve got a whole bunch of conflicting requirements. If it doesn’t solve a problem, it’s not an innovation. An additional nuance is the need to actually demonstrate that the innovation solved the problem. A hypothesis is not yet a solution. One has to prototype a proposed solution and show that it really does work.

The explicit callout to the value to customers drives home that an innovation must create a distinct benefit. If your customer doesn’t get value out of it then what’s the point? As it happens, I’m ok without these additional words. If there was no value in the solution, then how could there have been a problem to solve in the first place? The same goes for the customer: a problem is not a problem if no-one is experiencing it. Note that the customer in this case can be an internal or an external customer.

So why would we want it?

An underlying assumption when a team shies away from innovating, is often that there is already an existing solution. If that is truly the case, then this hesitation may be valid. More commonly, this assumption turns out to be false. We may have solutions in mind for each one of the requirements, but we’ve not quite figured out how to do it all at once. Maybe we can solve everything, but so can our competitors – maybe they already have – so there’s no competitive advantage. Maybe – just maybe – we’re optimistic enough to think that there might be an even better solution out there: a solution that exceeds all requirements with a bunch of nice-to-haves on top.

Keep in mind that if it was easy, everyone would be doing it!

So how do we make Medical Device Innovation happen?

In order to successfully innovate, there are a number of ingredients that really help.

Desire

The first ingredient is the desire to strive for innovation in the first place. This may sound obvious, but it’s surprising how often it’s not there. If deep down inside, you don’t really want to innovate, then it might be best to just not do it at all. The process of innovating is often long, risky and unpredictable. It will involve lots of trial and error, a bunch of failures and hopefully – but not necessarily – a final success. If there is a workable alternative to innovating, then you should consider it. If there isn’t one, then you should keep that in mind, especially in those moments of doubt!

Space

The next ingredient is space. One way to think of this is space within a program plan. Program plans are often faced with a ridiculous timeline, no budget, and impossible requirements. It’s almost comical. Holding too tight a rein on any of these dimensions will extinguish any chance of success. This is a real challenge; medical device startups shouldn’t underestimate the difficulty of fundraising and the steady cadence of milestones that fundraising often imposes. The hard truth is that if you can’t find room for your team to wrestle a tricky problem into some sort of shape, then they won’t be able to do it. People need some freedom from their day-to-day concerns about budget, timelines or performance targets. Without that space, your team will inevitably make choices that sacrifice performance for predictability. This may lead you to a plausible solution, but often to the wrong problem.

The flip side of innovation is risk. What we’re really trying to do is cordon off the risky area to avoid a huge catastrophe. What do you do if you’re going to try something risky? You ask someone to hold your beer. It’s the same thing here: your team will need enough time and budget in the plan so that they can experiment, prototype, fail and start over. Test out the big, risky things early on and maintain a backup plan whenever you can’t. Milestones need to take this into account too. I don’t mean gratuitous sandbagging, but don’t hail-Mary the whole program either.

Recently, during the planning of the next phase of an ongoing medical device development program, I was faced with a challenge relating to a quantification algorithm. Every other aspect of the device was sufficiently defined and understood to proceed with our next integrated prototype spin. This put the algorithm development squarely onto the critical path, causing day by day delays in the overall program. We still didn’t even know what the eventual computational demands would be. We knew that this algorithm would need its own processor module anyway, so instead of pressuring the team to hurry up, I defined clear data, power and volumetric interfaces for the module. This pulled the algorithm development right off the critical path, buying the team many months to complete their work.

Living the Problem

There is a common mythology that suggests innovative ideas strike like lightning bolts out of the blue. The reality is that you need to spend a year banging your head against the problem – through research, analysis, and experimentation. Even after the glorious thunderclap, you still have a bunch of testing and synthesizing to slog through to convince yourself that you’ve actually done it. During this period, it is most helpful to keep the team small and focused. A few people deeply immersing themselves in a problem-space is much more effective than many more people who are spread across many different programs. Constant task-switching is counter-productive.

Iteration

The odds of hitting upon the right solution on your first try are really slim. Even if you get it mostly right, you will still be doing it again (and again) in order to optimize. The process usually unfolds according to the following script: hypothesize a solution, do some analysis to see if it has legs, and then set up an experiment or build a prototype to try it out. Based on those results, go back and do it again, each time addressing more and more of the requirements. Keep iterating until you are convinced that you have really, truly found a solution.

Note that throughout these iterations clarity grows on what the true requirements are. Just like you can’t get the solution right the first time, you are also unlikely to get the requirements right, and that’s ok. Part of the iterative process involves checking the checks.

For a recent project, it was imperative to deliver working devices as soon as possible. A strategy of minimal iteration was employed, and bolstered by a large, multidisciplinary team, analyzing, reviewing and testing in parallel. We did succeed in producing a working device in record time. Looking back in hindsight, it took a ton of effort and was not nearly as quick as we might have hoped. For programs that are not under such extreme pressures, it would be significantly more efficient, and not take much longer, to have planned a series of prototype iterations, focusing first on proving out critical design choices and functionality and later on addressing the full set of requirements.

Psychological Safety

The term Psychological Safety pops up a bunch lately. From a business perspective, there is the possibility of budget or timeline over-runs, the total failure of a development program, or in extreme cases, the whole company. For the people involved, there is the risk of embarrassment, loss of face, loss of their jobs, even failure of their careers. All of these worries can choke the process of innovation. A culture of respect, trust, and security will ease these fears.

Innovating can be draining. The nature of the process means failing repeatedly, prior to success. Even the most self-confident individuals will go through periods of self-doubt and occasionally, downright fear. Persevere because you believe in the goal. Even the strong may waiver if not properly supported by their organizations, teams and colleagues. Failure of a hypothesis must not be perceived as a personal failure.

Leadership

An organization’s leadership plays a huge role in the ingredients that I’ve described above. This makes it the final one that I’ll mention in this blog. The process of innovation can be amplified by the optimization of corporate processes and company-wide management tools. Leadership can facilitate the growth of their employees’ skills, abilities, and judgement. It’s also up to leadership to reward and encourage innovative behavior, and de-incentivize counterproductive behavior. A powerful, yet subtle mechanism for leaders is to overtly model key innovative behavior, including controlled failure.

Summary

You may have noticed that I haven’t once described how to innovate. That’s a topic for a future blog. Often medical device innovation is blocked not because the wrong process or people were engaged, but because the wrong ingredients were present. If you optimize these for innovation, you stand a much better chance of success!

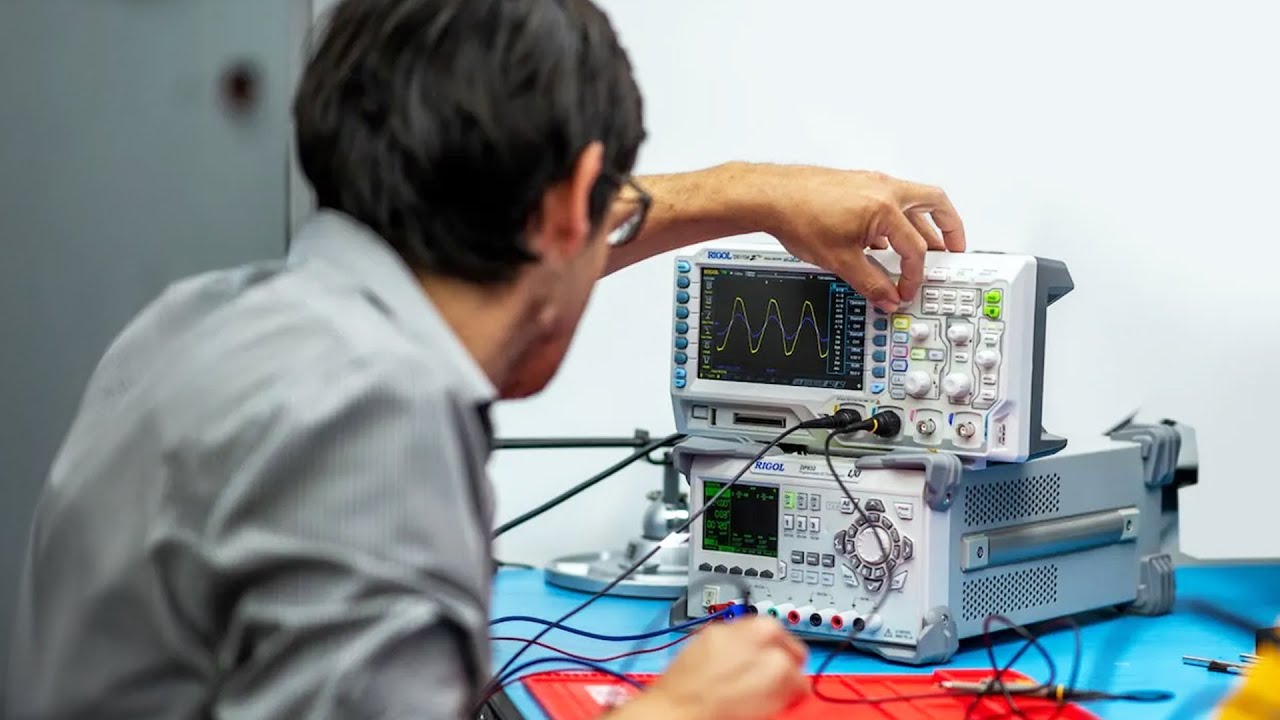

Image: StarFish Medical

Kenneth MacCallum, PEng, is a Principal Engineering Physicist at StarFish Medical. He works on Medical Device Innovation for a variety of areas including ultrasound applications. Kenneth would enjoy hearing from readers about their reference designs and experiences.