How to choose injection molding partners (Pt. 1)

Terminology, Process, Volumes, and Time

Selecting the right injection molding partner is crucial for a successful project. The costs and timescales can be a significant part of a project budget.

My two-part blog provides tips and considerations I have discovered and developed over many projects at StarFish Medical and other organizations. This blog will cover basics and part two will get into financials and quality considerations.

Understand Injection Molding Terminology

Like any profession, there are certain keywords and phrases with implied meaning. Product Developers usually use the phrase ‘low volume’ or ‘pilot volumes’ to mean tens to 100s of units. Most injection molders call 10,000 units ‘low volume’. Anything less is considered ‘prototype’ tooling, and volume is often a million parts.

Another important phrase is ‘cycle time’. This is the time it takes to mold a new part, and can be important if you want high volumes. Multi-cavity and family tools are also important phrases: the first being an injection mold that produces multiple version of a single design in one go, and the second being an injection mold that produces multiple different parts at the same time – there can be some overlap. The former is useful to increase the number of parts produced for a given cycle time, and the latter is useful when you wish to try and reduce your upfront tooling costs.

The main drawback of a family tool is that over the course of the product life, one part of the family may be obsoleted, leaving a suboptimal tool for the remainder of the parts.

Understand your Molder’s Process

Not all injection molders are the same. Some prefer steel tools, other prefer aluminium. Some prefer up and down, simple parts only, like a clamshell case. Some can deal with moving slides, others can deal with moving slides and collapsible sections, and yet others still are experts in seamless molding with no apparent flash lines (the area where the mold pieces push together).

Even then, master molders often surprise designers. For example, in the past I tried to second guess a molder and fully define models with draft angles (tapers to help the part come out) aligned to a particular orientation e.g. left to right. However, the tooler came back and pointed out that if I changed the side action orientation e.g. right to left, they could fit several parts in a family tool, significantly reducing up-front costs.

I now prefer to submit draft models for ballpark quoting with an indication that we need to use collapsing cores and bump offs where possible. I then go over each part piece by piece to get the tooler’s feedback.

The dialogue between molders and designers can eat up a lot of the clock. This is where designers learn the tooler’s drawing requirements, i.e. a fully dimensioned 2D drawing for first article inspection, or simply which critical control points need to be noted.

It’s all about the Volumes

Have a clear understanding of your volume requirements and how they are going to change over the life time of the product. For example, if your injection molding is a complex enclosure for a benchtop device and you intend to sell the product for 5 years (Product Manufacturing Lifetime, not device lifetime), sales volumes will typically follow a sigmoid curve – e.g. a hundred the first year, a thousand the second, thousands the third, then begin to ramp down as your new, improved products come to markets. This model requires tooling which can support up to 100,000 shots, and lower cost aluminium molds may be appropriate.

Contrast a purely injection molded device with a 10 year product lifetime for a disposable infusion set. Initially, this only needs a few hundred parts for clinical studies, then ramps up to tens of thousands, and several hundred thousand per year for the shoulder. Here, hard steel molds which can achieve 1,000,000 shots may be more appropriate, but initially are more expensive to manufacture.

Time, Time, Time

Setting up Injection molding tooling takes time. The reason for this is simple – injection molding is a complex process. The more money invested into the tooling, the longer you should take to get the tooling correct. Mold flow analysis, gating location, water line location, and parting line decisions are very important in determining whether the part created is what was originally intended.

There is nothing worse than spending precious capital on tooling, only to have it deliver sub-par parts. The first-off parts may not be exactly correct – gating, operational parameters, or other aspects may require alterations, all of which take time. This is an aspect of tooling which is not often considered.

Aluminium tooling is faster and can be as effective. But it is also less forgiving of mistakes or poor tooling decisions. The reduced time to make aluminium tooling means that you may still be able to fix some issues in less time than it takes to make one set of steel tools.

We`ve covered terminology, process, volume and time considerations for injection molding selection. Next week in part 2, I`ll tackle Quality considerations and the most important selection area of all– Cost-Benefit Analysis. I`d be pleased to hear from readers about their injection molding experiences and tips.

Vincent Crabtree, PhD is a former Regulatory Advisor & Project Manager at StarFish Medical. He learns from his mistakes and likes to share the knowledge.

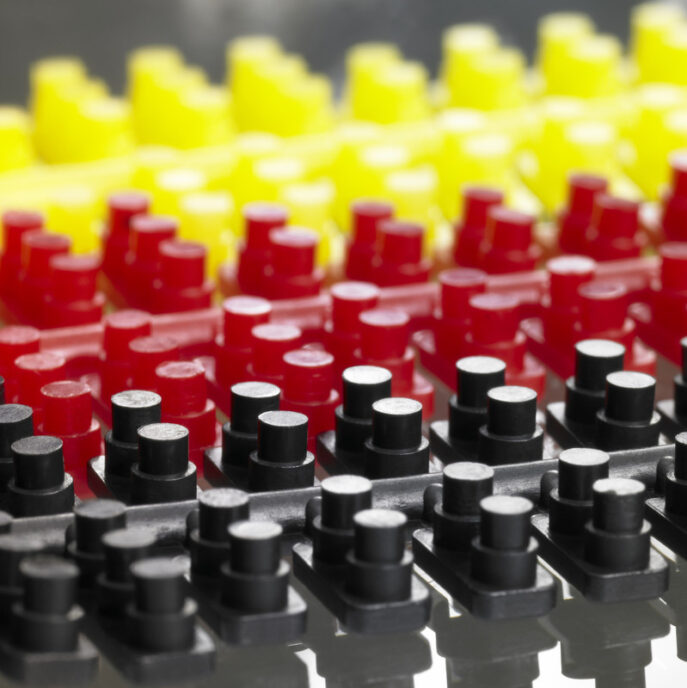

Image: 7649002 © prill / CanStockPhoto.com