Resource Centre

Discover a wealth of knowledge and insights from the experts at StarFish Medical. Our Resource Centre offers product development tips, reviews of new and cutting-edge technologies, and in-depth articles on regulatory updates and compliance in medical device development.

-

Understanding how clinical ventilator development differs from commercial ventilator design is essential for teams planning early studies.

-

Nick walks through a practical Teflon tape lesson that came from real work supporting a mechanical test rig.

-

Most sterile medical devices begin their journey long before anyone thinks about sterilization. Teams focus on function, usability, materials, and suppliers, then discover that sterilization constraints can reshape many of those early decisions.

-

After years of working with founders and technical teams, I have learned that early design missteps rarely come from engineering flaws. More often than not, they come from missing conversations.

-

Medtech founders operate with more constraints than most sectors. You are responsible for deep technical problem solving, high-stakes decisions, regulatory navigation, investor conversations, and a constant stream of operational tasks.

-

Consumer health prediction shapes more of daily life than most people realize. In this episode of Bio Break, Nick and Nigel explore how retail data can reveal health information without a person ever speaking to a clinician.

-

Every MedTech startup begins with a hypothesis, an idea that could transform patient outcomes, simplify delivery of care, or improve how clinicians diagnose and treat patients.

-

When Ariana Wilson and Mark Drlik take apart a common appliance, they uncover engineering principles that connect directly to medtech.

-

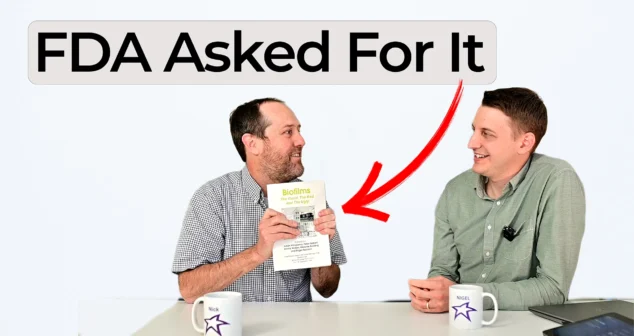

When reviewing evidence for a medical device, a single citation can shape an entire submission. In this Bio Break episode, Nick shares a biofilm referencing lesson that has stayed with him since the early 2000s.