7 Tips for Balancing Cost and Feedback

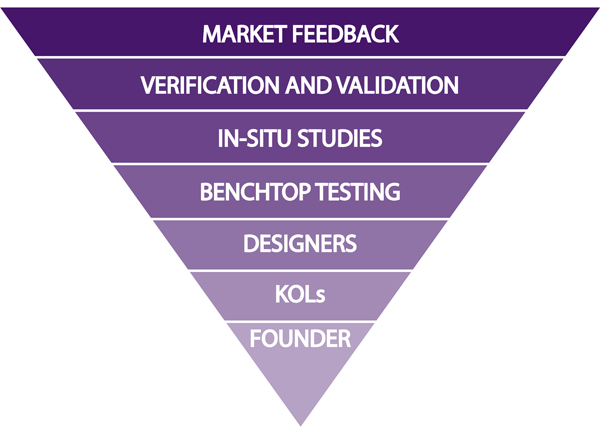

Balancing Cost and Feedback includes building an Input Pyramid to support your medical device development

As a medical device designer, I see clients balancing cost and feedback in a daily struggle to decide when to get clinical feedback, from whom, and how much weight to give that input. KOLs (Key Opinion Leaders) and individual designer experience can take a product well into conceptualization, but at some point you’ll realize you need to expand the group of people who have used the device, or risk basing your entire program on a sample size made up of just a few people.

Similarly, bringing intended user groups into the study early in the development plan can save you time but can be expensive, so finding a balance is, as always, the key to success. Without balance, your pyramid of input will certainly topple and your program may not have the funding needed to pick it up again.

Founding a Product

It is normal to start developing a medical device based on very few inputs, but it’s worth getting as much expert input as you can as soon as you can afford it to make sure your value proposition will one day turn into actual sales. KOL’s and intended user groups in the target market are key to early feedback, which can be the single biggest factor in the success of your medical device, essentially strengthening the foundation of your development.

Choosing your Horse

Excluding exceptional circumstances, it’s often a major financial risk to develop more than one medical device at once. You may get different feedback from your different KOLs, but you’ll likely have to pick and choose specific, particular feedback to focus in on an achievable set of indications to keep your device focused and achievable.

Get Feedback from Designers

Product designers can be fickle: they will want a set of fundamental requirements from day one, but will also have lots of input and suggestions of their own. Once the goal is understood and the environment established, their experience-based input is a major resource, so use your design team for feedback – they may be the largest group to review your device yet.

Go For the Low Hanging Fruit

It’s entirely possible that your device is so medically risky that clinical studies can really only be done near the end of your development, but it’s also possible that there are resources available to help you get a jump start with some benchtop testing. For example, if your device analyzes blood samples it’s not an overly difficult task to run human blood studies very early on due to the availability of blood for medical testing. Crowdsourcing can also be a cost effective way to get opinionated or quantifiable feedback from a wider group as well.

Look Like You’re almost Done – Even when You Aren’t

In-situ studies are a precursor to formal V&V or clinical studies, and can take the form of user studies (if the focus is usability) or opportunities for technical data (if technology is the focus), or both. ISO62304 and FDA guidance documents can help guide their structure respectively, but in both situations it’s best to try to bring a finished idea to the table. Quick, low fidelity prototypes help speed up the iterative design process as new information is learned from KOLs or user testing. Trying to ensure your touchscreen GUI format is understandable? Bring completed paper printouts and stick them up in a representative location. Trying to apply your sensor to a larger demographic of people? Hardwired cords and band-aids will do for now. Cheap is fine, just be cautious of leaving too many variables open that may bring into question the validity of your data.

Verify and Validate your Design

As soon as you’re closing in on a general solution, it might be worth guessing at the rest of the details to enable a complete prototype for early V&V. This prototype might have flaws or limited functionally, but it’ll be the first opportunity to catch surprises that you hadn’t thought of or correct assumptions that are wrong. Early V&V exercises may seem like an unnecessary expense, but they are a way to keep your input pyramid stable and avoid major findings on a completed design.

Feedback is never ending

Just because you have FDA approval and you’re firmly in the market doesn’t mean the feedback will stop. Some post-market feedback is nice to know but not important enough to take action over, where other times feedback will obligate a design change. Your regulatory experts will be able to help you know the difference and which input requires action.

Nigel Syrotuck is a StarFish Medical Mechanical Engineer and frequent guest blogger for medical device media including MD+DI, Medical Product Outsourcing, and Medtech Intelligence. He works on projects big and small and blogs on everything in-between. Have a topic you’d like “Nigel-ized”? Leave him a comment.

Illustration: StarFish Medical