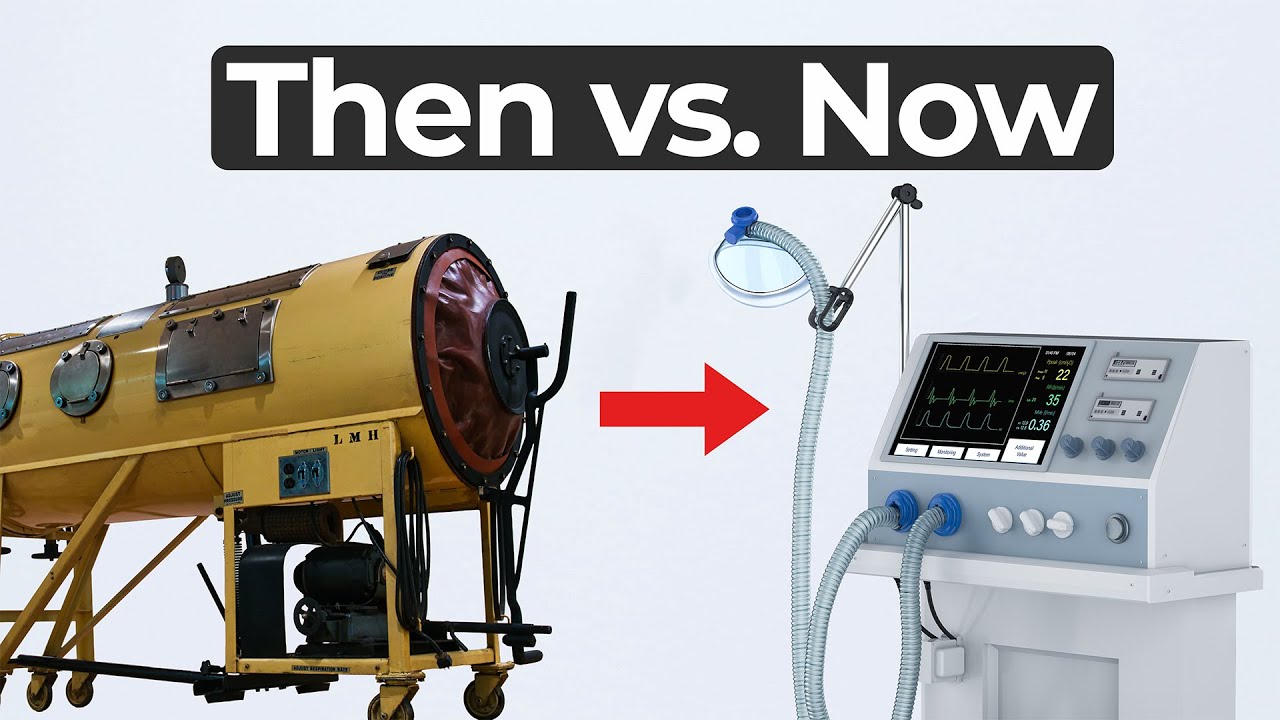

Iron Lung Innovation and Ventilator History

In this MedDevice by Design episode, Ariana Wilson and Mark Drlik take us back in time to explore iron lung innovation during the polio epidemic of the 1920s. Imagining themselves as engineers of that era, they discuss what tools and ideas could have saved lives in a world without modern ventilators, penicillin, or even bubble gum.

With automobiles, planes, and submarines already in use, the technology of the 1920s offered opportunity—but also limitations. Ariana and Mark begin with the iron lung, a large negative pressure device that encased the entire body. While effective at simulating natural breathing by allowing the chest to expand, it was restrictive, immobile, and deeply uncomfortable.

Rethinking Respiratory Innovation

As the conversation evolves, the team explores alternatives. Could a smaller “iron lung mini” have worked? Could thoracic-only negative pressure devices have made care less invasive? What about exoskeletons or diaphragm pacing systems?

They also reference more recent technologies like those from Curious and AirAD, and how modern companies such as Lungpacer have experimented with stimulating the diaphragm directly. But in the end, it’s clear that iron lung innovation was well suited for its time—even though today’s ventilators use positive pressure systems that introduce new performance metrics and control options.

Why the Iron Lung Still Matters

This episode isn’t just a history lesson. It’s a reminder that engineering choices are shaped by the needs, tools, and constraints of their time. While today’s ventilators provide advanced feedback and control, they’re not always more physiological than their century-old predecessors.

Watch as Mark and Ariana explore mechanical ventilation from past to present—and imagine what they would have built as medtech engineers in 1920.

Enjoying MedDevice by Design? Sign up to get new episodes sent to your inbox.

Related Resources

Nick and Nigel walk through how sterile disposables are processed and verified before they reach the field.

The FDA agentic AI is making headlines after the agency announced its own internal AI review tool. In this episode of MedDevice by Design, Ariana and Mark discuss what this could mean for medical device submissions and regulatory efficiency.

The sandwich ELISA assay is one of the most common ELISA formats used in diagnostics. Nick and Nigel walk through the method step by step using simple visuals and plain language.