Let’s talk about what an anodized finish actually is.

A core finishing technique around the world, anodizing is highly valued in the medical industry to promote longevity of devices. It is a finishing process that can be applied to a few different materials, the most common being aluminum (in fact, this blog will only discuss aluminum anodizing).

Anodizing thickens the oxide layer (Al2O3) found naturally on aluminum parts by about 100-10,000x. This means that anodization actually converts some of the aluminum, as opposed to paint, which just sits on top.

Anodizing also provides a finish that is more corrosion and scratch resistant, slipperier, and easier to adhere to or paint than the untreated alloy. It is also electrically insulating and can change the aesthetic appearance drastically.

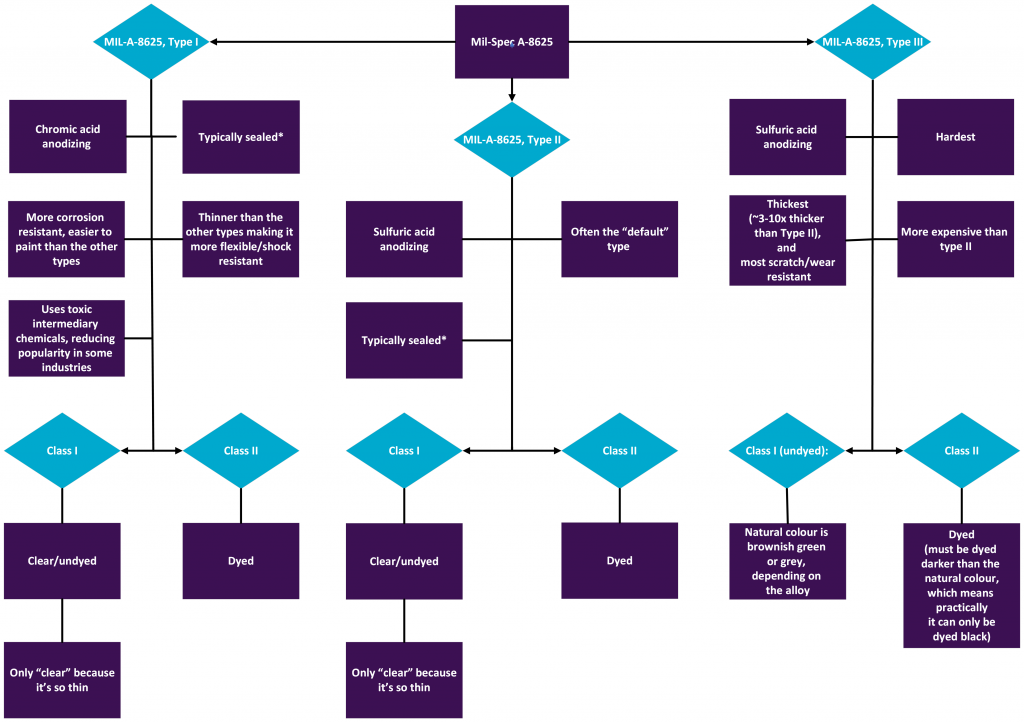

The cost is often on par with painting and leaves a durable coating that has desirable aesthetics if finished well. That being said, there are different types and sub-types of aluminum anodizing that can get confusing, so it is important to know the differences. In North America, Mil-Spec A-8625 is a very common standard and is the focus in this blog:

*Type I and II must be sealed unless stated otherwise (per MIL-A-8265) after conversion. Type III can be sealed as well, but sealing negates the ability of the material to retain lubricant, so Type III is often left unsealed. Depending on how the part is sealed (the sealer can use boiling de-ionized water, which is energy intensive, or a variety of chemical seals that work at room temperature). The top layer of coating might not actually be Al2O3, which is an important distinction for biocompatibility

It’s interesting to note that Chromate Conversion Coating (trade name Alodine) – despite sounding similar and also being governed by Mil Specs – is not a form of anodizing. A big difference is that alodine is a conductor. To make matters more confusing, you can actually apply both on the same part. The alodine is done first and then parts are masked for anodizing. The anodizing process dissolves any unmasked alodine, resulting in discrete areas of conductive and non-conductive coating, rather than a double layer across the whole part.

For the sake of completeness, MIL-A-8265 Types 1B, 1C, and IIB also exist, but as they are not as common, they are not covered here.

I hope this has been a helpful guide to understand the basics of the features and benefits of different types of commonly specified anodized coatings in North America. Happy finishing!

For more insights on this topic, read our blog on Tips and Techniques for Anodizing Medical Devices.

How Much Does it Cost to Develop a Medical Device?

Image: StarFish Medical

Nigel Syrotuck is a StarFish Medical Team Lead Mechanical Engineer and frequent guest blogger for medical device media including MD+DI, Medical Product Outsourcing, and Medtech Intelligence. He works on projects big and small and blogs on everything in-between.

Learn more: Is Anodized Aluminium Biocompatible?