Resource Centre

Discover a wealth of knowledge and insights from the experts at StarFish Medical. Our Resource Centre offers product development tips, reviews of new and cutting-edge technologies, and in-depth articles on regulatory updates and compliance in medical device development.

-

Ariana and Mark examine the complexities of endoscope reprocessing, one of the most difficult tasks in medical device hygiene.

-

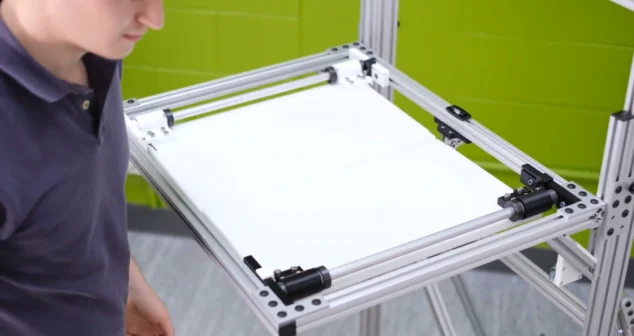

Medical device drop testing helps ensure that products and packaging survive real-world handling. We demonstrate in-house drop testing on an actual device and its packaging using a custom-built drop tester.

-

Medical device startups/founders and enterprise partners have unique strengths and goals, which are often reflected in the way they work with CDMO (Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations) partners.

-

In the highly regulated world of medical device development, ensuring product safety, quality, and compliance is essential. One critical yet often overlooked aspect of this process is test method validation (TMV) in medical device development.

-

A structured, well-documented design review process is a critical component of successful product development, particularly in the medical device industry.

-

In medical device development, we deal with complex projects that span multiple disciplines, timelines, and regulatory gates. It’s a constant balance between moving fast enough to innovate, but slow enough to stay compliant.

-

Ariana and Mark walk through FDA-approved options and explain how to select the right one for your product. From metals to plastics and electronics, not all devices can handle the same process.

-

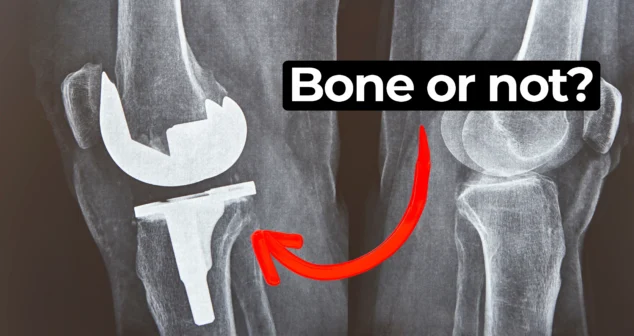

In this episode of MedDevice by Design, Ariana and Mark dive into the biomechanics and materials science behind osseointegration for implants.

-

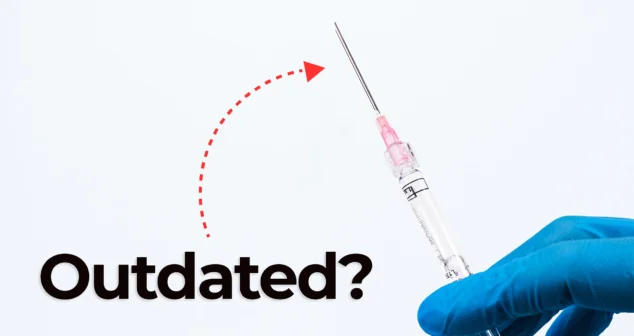

Nick and Nigel dive into the world of jet injector drug delivery. This needle-free method, made popular in science fiction and real-world vaccines, is still used today.