ISO 10993-1 FDA Change Could Significantly Impact your Biocompatibility Plans

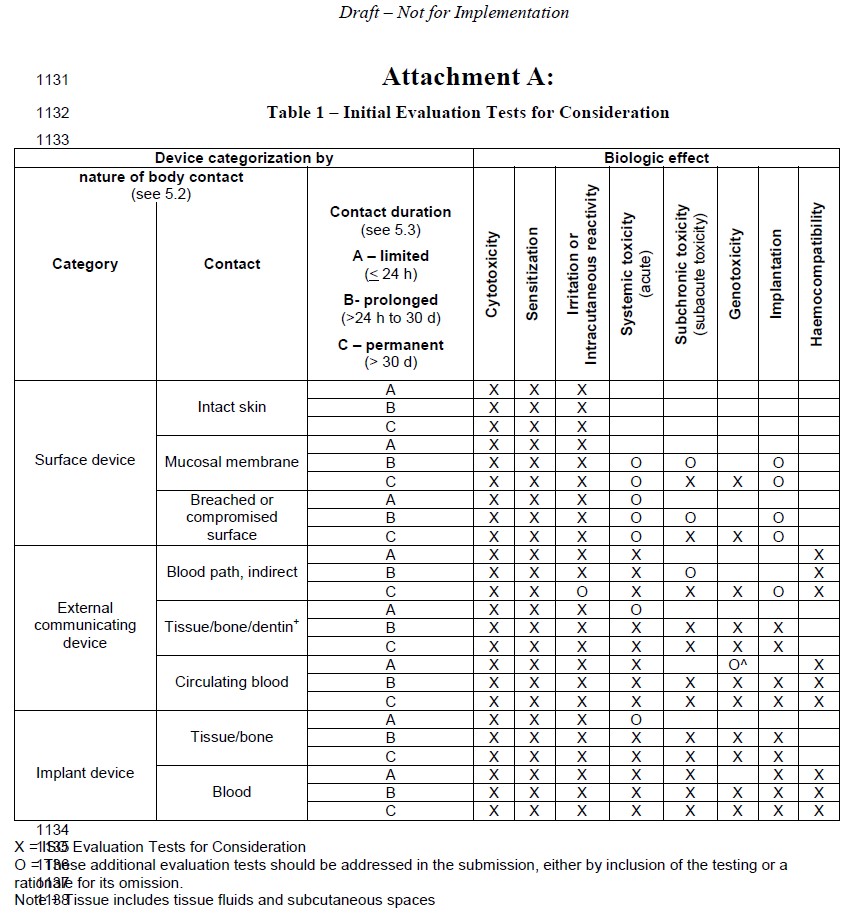

The FDA released a proposal to change the guidance document for ISO 10993-1 in April of this year (2013). Most of document UCM348890 seems straight forward – things like implementation details associated with genotoxicity, how to go about labeling your device as BPA-free, and a logical workflow diagram, were updated… However, once you work all the way down into Attachment A, it reveals some significant changes to the standard.

The implementation details associated with many changes proposed in the draft guidance document are becoming familiar with reputable test houses. But the financial ramifications of additional testing for specific device categories may not be familiar to medical device developers and will be impactful. These changes are best summarized with the chart below, with a new marking indicated as ‘O’s not in previous standards. For example, devices making contact with breached or compromised skin for 1-30 days will now likely have to conduct subchronic toxicity – depending on the nature of the test and selected protocol this can be in the neighborhood of $40k per iteration – just for one test, excluding prototype and internal communication costs, and assuming no failed attempts.

Some of the proposed changes make sense, for example, external communicating devices contacting tissue/bone/dentin could require additional testing. Given the intent of the FDA to keep us humans safe, I could brainstorm a few applications that I would want to see systemic toxicity be conducted.

However, having to conduct an implantation study for something like temporary nasogastric intubation (mucosal contact for >24h) seems extreme. The footnote in the proposed standard change ‘provide rationale for its omission’ leaves subjectivity to both the applicant and the FDA auditor to be able not to conduct these additional test. If the device is being applied for as part of a 510(k) submission, and does not utilize novel materials – does this constitute acceptance that the ‘optional’ tests do not need to be conducted? Or perhaps it is subjective towards the use case and environment, and can be mitigated through the Risk Management File?

The general edict from the FDA is risk reduction through management. But I think the easiest way to stratify the applicability of these additional tests falls into the guise of how the applications come in. If it is a PMA, do the additional tests. If it is a 510(k), and there is a history of similar predicates, don’t do the additional tests. If you’re somewhere in between, then the revamped DeNovo process comes to the rescue: If specific guidance documentation is available – it overrides the above. This would leave less subjectivity in budgeting and scheduling to medical device developers, and avoid awkward discussions on how to interpret the standard.

If you have opinions on the proposed changes to ISO 10993 or how to best bring your product through the rigors medical device approval, I would be glad to hear from you.

Mark Drlik is a Concept Development Manager at StarFish Medical. He frequently works with colleagues in Regulatory Support on issues like those in the proposed ISO 10993-1 change to understand how his medical device projects are impacted.

Images: StarFish Medical

Read a review of the FDA Guidance on Using ISO 10993-1 integrating biocompatibility evaluation within the risk management process, as outlined in the FDA Guidance Document Use of International Standard ISO 10993-1, Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process.

Designing a medical device, but not sure whether it needs to be biocompatible? Check out A design engineer’s perspective of medical device biocompatibility.