Data Management Is Now a Core Device Requirement

TL;DR

- Connected medical devices now assume data collection and cloud connectivity.

- HIPAA, PIPEDA, and GDPR impose different but overlapping data protection obligations.

- Data minimisation, anonymisation, and encryption should be designed in early.

- Access controls and audit trails must balance safety, usability, and security.

- Device architecture must support patient data access and deletion rights.

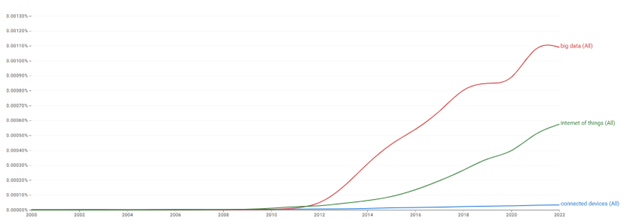

When I was starting out in medical devices, the discussion focused on the possibility of an internet of things and the promise of “big data” about everything.

Today, connected devices are the expectation rather than a future state. My fridge, washing machine, and even my cat’s litter box can connect to the internet, whether I want them to or not.

Medical devices are no different. From monitoring drug delivery devices to ensure compliance with medication regimens, to symptom monitoring and reporting directly to healthcare providers, data collection and cloud-based systems are now assumed. At the same time, healthcare institutions are under pressure to manage capacity by shifting more treatments and monitoring activities back into the community. The result is a growing class of “home -based” devices, a term that is something of a misnomer since these devices may be used anywhere outside a clinical environment, including schools, gyms, stores, or vehicles. This shift is reflected in how the industry talks about connected medical devices, as shown in the chart.

I have written previously about regulatory expectations around software documentation and cybersecurity. in this blog, I focus specifically on what is required when handling the data itself.

Data Privacy Regulations Device Teams Must Understand

In this blog, I have limited the scope to data privacy and data protection requirements in the United States, Canada, and Europe.

Europe was the first to publish a formal data protection framework with the Data Protection Directive in 1995 (95/46/EC).

The United States introduced the Privacy Rule and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in 1996.

Canada followed with the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) in 2000.

All of these frameworks have evolved over time. The most significant change was the transition in Europe from the Data Protection Directive to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (2016/679).

Within the EU, Directives provide guidance that must be enacted into local law by individual member states and can be adapted. Regulations, by contrast, are mandatory and apply as written across all member states. Because GDPR governs where data is collected and processed, it can still apply to products developed for or deployed in other markets. The following sections provide a brief overview of each regulation and highlight key differences that affect medical device design.

HIPAA and Medical Device Data Responsibilities

HIPAA applies specifically to health data and health records, rather than personal data more broadly.

US laws and regulations are published in the Code of Federal Regulations, available at www.ecfr.gov. HIPAA requirements are found in Title 45, which covers Public Welfare, specifically parts 160 and 164.

Part 160 defines enforcement mechanisms, while part 164 outlines technical and operational requirements. Part 164 includes the following categories:

- Administrative Safeguards: which address how healthcare organizations collect health data and how their workforce must handle it

- Physical Safeguards: which relate to protecting the device and the data it stores from physical access

- Technical Safeguards: which include access controls, authentication, and audit trails embedded within the device

- Organizational Requirements: which govern how health data is used and shared

- Policies, Procedures, and Documentation: which define required evidence of compliance

- Breach Notification requirements: which describe how organizations must respond to and communicate data breaches

PIPEDA and Personal Data in Medical Devices

PIPEDA extends beyond health data and applies to all personal information, while explicitly identifying personal health information as a sensitive category.

PIPEDA is a Federal regulation, but provincial and territorial privacy laws may also apply. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada notes that many of these laws are deemed “substantially similar” to PIPEDA, which is why they are not covered in detail here.

PIPEDA defines ten fair information principles:

- Accountability

- Identifying Purposes

- Consent

- Limiting Collection

- Limiting Use, Disclosure, and Retention

- Accuracy

- Safeguards

- physical measures, such as locked filing cabinets and restricted office access

- organizational measures, such as security clearances and need-to-know access

- technological measures, such as passwords and encryption

- Openness

- Individual Access

- Challenging Compliance

GDPR Implications for Connected Medical Devices

GDPR applies to all personal data and provides additional protection for health data. It governs data collected in the EU, regardless of where that data is processed.

GDPR defines three key roles:

- Data Controller, the organization that determines why and how personal data is collected

- Data Processor, the organization that processes data on behalf of the controller

- Data Subject, the individual to whom the data relates

Under GDPR, data subjects have the right to access their personal data, correct inaccuracies, request deletion under certain conditions, export their data in specific circumstances, and object to or restrict certain uses. these requests must be handled within defined time limits.

Article 5 of GDPR defines the core principles for processing personal data. Personal data must be:

- processed lawfully, fairly, and transparently

- collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes

- adequate, relevant, and limited to what is necessary

- accurate and kept up to date

- retained only as long as necessary for the intended purpose

Designing Connected Medical Devices for Data Protection Compliance

The controls required to meet these regulations fall into two categories:

- Actions implemented within the design of the product

- Actions taken by those using the product or handling the data

The second category includes documentation, processes, and training for users, healthcare practitioners, and infrastructure teams responsible for the environments in which devices operate. Manufacturers must clearly communicate what data is collected and what cybersecurity controls are required, but responsibility for broader organizational compliance typically rests with those deploying the device.

As a result, this discussion focuses on what can be addressed through device design.

Cybersecurity Hardening for Connected Medical Devices

When an entity attempts to access a device, it is typically for one of two reasons: to disrupt device performance or to extract stored data.

Devices should be protected to the greatest extent possible without compromising safety or effectiveness. Cybersecurity risk assessments should consider vulnerabilities at the time of design and throughout the product lifecycle. This requires ongoing monitoring for new vulnerabilities and a clear understanding of the software bill of materials (SBoM) for the product.

Routine penetration testing should be carried out to confirm that vulnerabilities are not accessible and that software updates are deployed correctly.

Anonymization and Encryption in Medical Device Data

Data protection starts with collecting only what is necessary. Fewer data fields reduce exposure, simplify storage and transmission, and lower the risk of privacy breaches. Each proposed data element should be critically reviewed to confirm its necessity.

Where possible, health data should be collected independently of patient identification. HIPAA’s Safe Harbor Method provides a useful reference, defining 18 identifiers that must be removed for data to be considered de-identified, including names, detailed geographic information, dates tied to individuals, contact information, identifiers, biometric data, images, and IP addresses.

If patient identification must be collected alongside health metrics, pseudonymisation may still be possible.

Pseudonymisation is a technique that replaces information that directly identifies people, or de-couples that information from the resulting dataset. For example, it may involve replacing names or other identifiers (which are easily attributed to people) with a reference number. This is similar to how the term ‘de-identified’ is used in other contexts. For example, removing or masking direct identifiers with references, such as collecting heart rate data for “Patient AB1, female, age 45.”

For larger-scale commercial data collection, more advanced pseudonymisation techniques should be considered, including hashing, encryption, and tokenisation.

Encryption methods include:

- Symmetric Encryption (Uses the same key for encryption and decryption)

- Asymmetric Encryption (Uses a pair of keys (public and private))

- End-to-End Encryption (Data is encrypted from the sender to the receiver)

The UK’s Information Commissioners Office and the Spanish Data Protection Agency provide useful context on selecting and applying these techniques appropriately.

Access Controls and Authentication in Medical Devices

Access controls may be procedural or embedded within a device interface. The appropriate approach depends on context of use and the balance between safety and data protection. Emergency-use devices may need immediate access, while diagnostic or monitoring devices collecting sensitive data typically require stronger data protection controls.

Access controls should reflect the range of expected users and their roles. A basic implementation may include general user access with limited functionality and administrator or clinician access with broader permissions.

Authentication mechanisms should ensure users are who they claim to be. Multi-factor authentication and strong password policies are increasingly expected. These requirements should be communicated clearly through the device interface or supporting documentation.

Audit trails are also essential. Devices should record access to data and changes to settings so that inappropriate or malicious activity can be detected and investigated.

Data Access, Export, and Deletion Requirements

Many data protection regulations grant individuals the right to access their own data. Device architectures must support secure export of patient-specific data and, in some cases, secure deletion upon request.

These requirements should be considered early, as retrofitting data access and deletion capabilities can be costly and complex.

Designing Medical Devices with Data Protection in Mind

Connected medical devices that collect personal data are now standard across the industry. Designing these devices requires careful consideration of how they will be used and how they support healthcare organizations in meeting data protection obligations.

As with any regulatory requirement, addressing data privacy and protection early in development and capturing those needs in product requirements reduces risk and avoids costly redesign later.

References and Resources

Links to the referenced regulations

- HIPAA eCFR :: 45 CFR Part 164 — Security and Privacy

- GDPR Regulation – 2016/679 – EN – gdpr – EUR-Lex

- PIPEDA Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

Useful resources about this topic

- Government sites about regulations

- Anonymisation

- General

Helen Simons is a Director of QA/RA at StarFish Medical. Helen’s education is in Mechanical engineering, with a background of product development and QMS development across multiple industries with consumer and industrial products to medical devices, IVD and combination devices.

Images: Adobe Stock

Related Resources

The FDA agentic AI is making headlines after the agency announced its own internal AI review tool. In this episode of MedDevice by Design, Ariana and Mark discuss what this could mean for medical device submissions and regulatory efficiency.

For manufacturers of novel devices that can make a significant impact to patient health, the goal of the program is to offer a path to streamlined and potentially faster market entry without sacrificing the rigour around ensuring safety and performance.

When I was starting out in medical devices, the discussion focused on the possibility of an internet of things and the promise of “big data” about everything.

With the release of ISO 14644-5:2025, Cleanrooms and associated controlled environments, Part 5: Operations, the standard places increased emphasis on operational discipline, human factors, and contamination control behaviour.